Fixing a $200 million backlog: Wake County students want to modernize school system’s HVAC units

Upgrades to newer, high-efficiency heating, ventilation and air conditioning technology aren’t in the cards for the Wake County Public School System, where a $200 million maintenance backlog has plagued the schools. Frustrated students have been pushing the school district for new HVAC technology — highlighting the district’s many troubles with HVAC systems –- as a…

Upgrades to newer, high-efficiency heating, ventilation and air conditioning technology aren’t in the cards for the Wake County Public School System, where a $200 million maintenance backlog has plagued the schools.

Frustrated students have been pushing the school district for new HVAC technology — highlighting the district’s many troubles with HVAC systems –- as a part of a larger push for a “Green New Deal” for schools that they believe will be cheaper in the long run for the district’s financially troubled maintenance department.

School district leaders have met with the students, but have told WRAL News they are wary of making the investment. Heat pumps, for example, cost more on the front end than traditional boiler and chiller technology and would require a building retrofit in existing schools, but they would drastically reduce energy costs over time, eventually making them cheaper.

Last school year, dozens of schools in Wake County called off at least one day of classes because of HVAC issues. Students say that oftentimes, even when school doesn’t get canceled, the extreme heat or extreme cold inside their classrooms makes it difficult to focus on lessons and tests.

“There’s so many times where the temperature in one class will be really hot, the temperature in another class will be really cold,” said Kriti Pokhrel, a recent graduate of Panther Creek High School, who helped lead a group of students that has attended numerous school board meetings and met with district officials and school board members to push for more energy-efficient technologies in the schools.

Sometimes classes get moved to other rooms when the temperatures are uncomfortable, such as cafeterias, Pokhrel said. Warm temperatures caused rashes on one of her friends.

Experts are split about how practical it would be for schools to change their traditional boiler and chiller HVAC systems. However, the cost of installing newer technology, such as heat pumps that both warm and cool indoor spaces, is less than it used to be thanks to new federal incentives that will last until at least 2035.

“Electric heat pumps are much more efficient,” said Anisa Heming, director of the Center for Green Schools. “They are definitely well-tested technology that can work really well in schools.”

They used to cost more than traditional HVAC systems, but new incentives under the 2021 Inflation Reduction Act allow schools and nonprofits to receive “direct pay” cost reductions that make the installation cost more comparable to traditional systems now, Heming said. The new One Big Beautiful Bill Act has removed many of the incentives for so-called “greener” technology, but kept in place the direct pay provision for schools and HVAC technology.

“We definitely promote installing newer, better technologies in schools, but we also understand that school districts are operating on limited budgets, and there are options for any system to be healthier and more efficient,” Heming said.

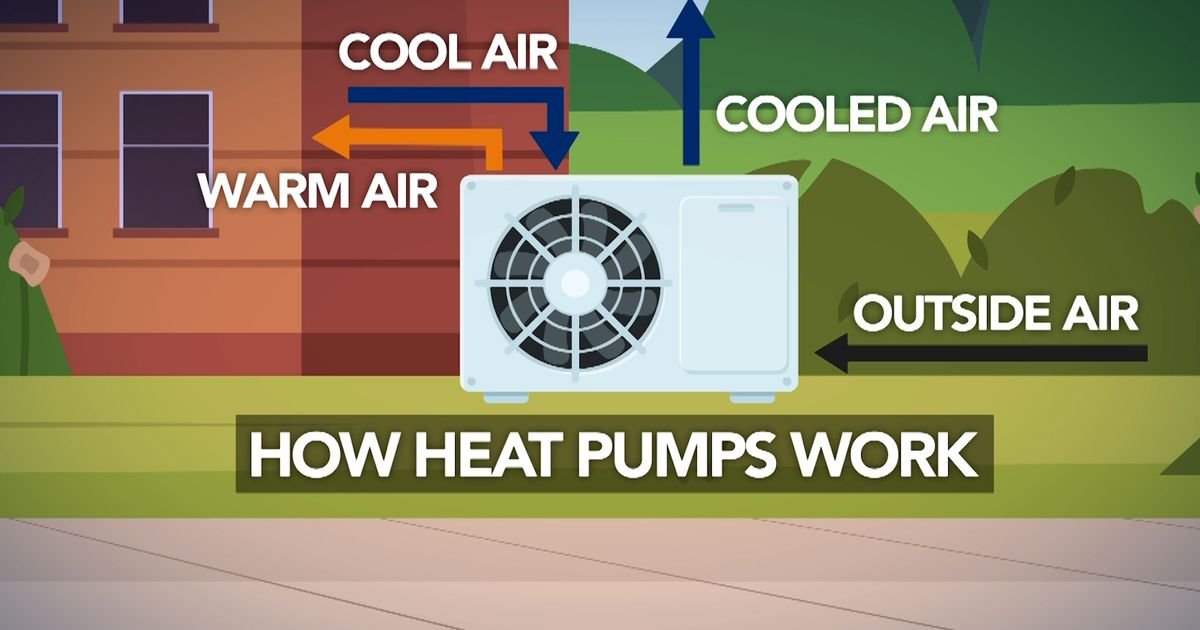

Heat pumps transfer heat from one location to another, rather than generating it. They use electricity and refrigerants to operate. Boilers use gas or oil to warm buildings, and chillers use refrigerants.

Although boiler and chiller technology is old in concept, it’s advanced quite a bit over the years, with newer units becoming more energy efficient, said James Freeman, a professor at Wake Tech Community College, who is also the program director of the air conditioning, heating and refrigeration technology program. Newer units and associated equipment can now better target where heat or cool air are needed more, Freeman said. So they can generate huge cost savings, compared to the older systems the district is struggling to keep up with replacing and maintaining.

“They’ve become way more efficient,” Freeman said. “The energy savings are substantial. Their ability to target areas is super beneficial.”

Heat pumps, he said, are “probably not practical for a school system.”

But more and more schools are turning to heat pumps for their HVAC systems, often starting small in elementary schools.

In the past few years, several elementary schools in Connecticut have been built with geothermal heat pumps — a type of heat pump that uses ground sources and wells, rather than air, to heat or cool.

Seattle Public Schools remodeled 15 schools and installed geothermal heat pumps and saw 30-77% reductions in energy use, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. It’s unclear how those reductions translate into dollars saved.

Harvard University researchers estimated the savings for one school in Massachusetts switching to a ground-source heat pump would be $14,000 annually, while also reducing air pollutants breathed in by people at the school and in the vicinity.

But it’s not about dollars for Kriti Pokhrel or her peers, who argue that the Wake school district needs to consider lower-emissions and more efficient technology to lower expenses in a cash-strapped part of the budget and to reduce the district’s effect on a changing climate that only puts more pressure on schools’ HVAC.

“This isn’t something that I’m theoretically reading about. It was something that’s happened to my school and me personnally,” Pokhrel said.

‘It’s the budget component’

Wake’s director of maintenance and operations, Mark Strickland, said the up-front cost — which could be a few million dollars for just a handful of schools — is a problem and why the district isn’t more interested in the technology.

“Mainly, it’s the budget component of it,” Strickland said. The district plans facilities work years in advance and has to leave room for cost increases as they happen. Plus, he said, the district may need more space to install certain types of heat pumps, such as ground-source heat pumps, that not all schools necessarily have.

“We had looked at some different things at a recent school project, but it was just not within our budget,” Strickland said. The district is currently look at ground-source heat pumps at a future school, but at just one school, he said.

He acknowledges newer technology can save money, but also that he’d have to hire more people to work with it.

“Think about cars,” Strickland said. “Newer cars get better gas mileage, so likely so that the newer technologies would increase our efficiency again, we have to transition to that newer technology with the staff that we have, and we’re understaffed now, so part of the conversation is, as we move forward and gain additional staff, we can recruit those people that have experience with those newer technologies.”

Without additional staff to handle the district’s current-day problems, he said, he’s hesitant to move forward with “anything out of the box.”

The boiler and chiller system is so far reliable, he said.

“It is a workhorse of a system, and when properly maintained, they work well,” Strickland said. “That’s why other hospitals and places like that would use a similar type system. So it’s tried and true for large buildings like we build. And there could be some technology coming that might change the direction that we’re going in, but we haven’t seen it yet.”

Still, the district has $200 million in deferred maintenance on its boilers and chillers, meaning they are not ideally maintained. It’s the result of years of budget priorities placed elsewhere than the maintenance department. The district has doubled its annual spending on maintenance to catch up, going from about $20 million two school years ago to about $40 million last year and this year.

The North Carolina House of Representatives budget proposal includes $500,000 for the Wake school system to identify “high-efficiency, next-generation heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems (HVAC) and chiller solutions.”

However, lawmakers have failed to pass a new state budget despite their July 1 deadline to do so — meaning that as the new school year kicks off, not only will teachers be without promised raises, but other state funding for school construction, or projects like that HVAC study, have been left in limbo. Because it’s pending legislation, the district declined to comment on it.

Nationwide HVAC backlog

HVAC maintenance is a problem to varying degrees nationwide, too.

A 2020 U.S. Government Accountability Office report found that 41% of school systems needed to update or replace HVAC equipment in at least half of their schools. The federal watchdog found that malfunctioning HVAC caused mold and other damage in some schools and caused some schools to temporarily close or adjust schedules. That was the case with Alamance-Burlington Schools, which delayed the start of the 2023 school year after insufficient airflow and high humidity contributed to toxic mold problems.

Many school systems across the nation have been busy updating their HVAC systems since the 2020 report, however.

The influx of billions of dollars in federal stimulus dollars during the COVID-19 pandemic helped some districts shore up at least some of their HVAC systems.

The U.S. Green Building Council found in 2022 that school districts were spending more of those dollars in HVAC than on other facility expenses, with $5.5 billion planned by mid-2022. Those funds largely expired Sept. 30, 2024.